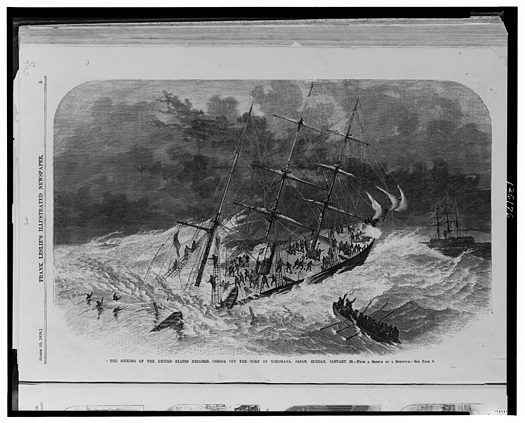

Sinking of the USS Oneida

On January 24, 1870, as she departed the port city of Yokohama on her return voyage to the United States, the USS Oneida was struck by the British Peninsular & Oriental (P&O) Line Steamer Bombay. The collision severely damaged the Oneida, which sank within about fifteen minutes, taking with her at least 115 sailors (20 officers/95 enlisted men). Among those lost at sea were at least eight Chinese and six African American crew members. Another 61 sailors (4 officers/57 enlisted men) were able to reach shore in the only two of the Oneida‘s lifeboats that were fit for launch. Japanese, Russian, French, British, and U.S. vessels in the vicinity later attempted to assist with rescue and recovery operations. As officials endeavored to provide explanations to grieving families and outraged Americans, the somber roll call, along with survivor testimonies, appeared in the hearings of the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General and Executive Documents of the U.S. House of RepresentativesExternal. (Ex. Doc. No. 236, 41st Congress, 2nd Session).

The USS Oneida was a screw-driven sloop-of-war launched in 1861 and commissioned in 1862. A Mohican-class vessel, the Oneida served in the West Gulf Blockading Squadron operations during the Civil War. Eight of her crew were awarded the Medal of Honor for actions during the 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay. After the war, the Oneida was recommissioned in 1867 and assigned to the Asiatic Squadron.

The disaster sparked a controversy that encompassed the assignment of blame for the collision, the subsequent actions of the Bombay, and whether more lives could have been saved. Among the contradicting testimonies of those aboard the Bombay and Oneida were opposing accounts of the exact circumstances leading up to and during the impact. They also emphatically disagreed over the specific distress signals, or lack thereof, implemented by the Oneida after the collision. The topic was hotly debated in official forums and public discourse, with Americans outraged over what seemed a callous disregard for human life on the part of the British ship, which had left the scene without any attempt to offer aid. Meanwhile, the British maintained that the American ship had both caused the accident and failed to indicate their distress.

A British Court of Inquiry decided on February 12, 1870External, that the Oneida crew was responsible for the collision, but censured Captain Eyre of the Bombay for not “waiting and endeavoring to render assistance.” A subsequent U.S. Court of Inquiry provided an opinion on March 2, 1870External, which placed all blame for both the collision and desertion on the Bombay, but did fault Captain Williams of the Oneida for failing to replace lifeboats that had been lost in a typhoon the previous August.

Memorials to the Oneida crew were dedicated in Japan. CenotaphsExternal marking empty graves were placed in family lots across the United States to remember husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers among the tombstones of their relatives.

In April 1870, distraught Oneida-survivors arriving in San Francisco(6th column) expressed their grief and fury, with at least one sailor asserting he was ready to reenlist if the U.S. would declare war against Britain in retaliation. Community fundraisers were underway in Boston and Philadelphia by May 1870, to benefit the orphaned children of Captain Williams(3rd column). A year later, American naval officers attended Russian ceremonies in New York City, honoring the Tsarevich (heir to the Tsar) upon the birth of his son, as a show of gratitude for that country’s efforts to recover the lost men of the Oneida(4th column).

Learn More

- The most reliable list of all those aboard the Oneida at the time of the disaster was ascertained from the survivors immediately after the wreck and submitted as evidence to the U.S. Court of Inquiry. The list identifies 115 lost (20 officers/95 enlisted men) and 61 survivors (4 officers/57 enlisted men). It also distinguishes race and nativity for eight Chinese and six African American crew members lost at sea.

- The original handwritten document is filed in case no. 4638, Loss of the United States Steamer Oneida; Court Martial Records, 1868-71; Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy), Record Group 125; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- A transcript of the list, with some name and spelling alterations, is included in U.S. Congress, Executive Documents Printed by Order of the House of Representatives During the Second Session of the Forty-first Congress, Vol. 11, No. 236External. (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1870), Part 1, pages 3-5.

- The Library’s Research Guide USS Oneida Disaster provides strategies for engaging this moment in history through the records of the individual men who are forever connected to the Oneida’s tragedy. Read newspaper articles from their hometowns; track down their personal correspondence and the military pensions distributed to their dependents; visit the memorials and cenotaphsExternal created by mourning family and comrades to honor their memories; and learn more about the history of the ship during its Civil War and Asiatic service.

- Read John Phelan and the Sinking of the USS Oneida posted in the Library of Congress blog Timeless: Stories from the Library of Congress.

- Library of Congress collections demonstrate the public interest and reaction to the USS Oneida disaster.

- Illustrations from popular periodicals published in 1870, spoke to the outcry over the tragedy: “The Sinking of the United States Steamer Oneida…from a Sketch by a Survivor” and “The Sinking of the Oneida by the Bombay“

- A pamphlet, also published the year of the collision, provided over 40 pages of specific details to readers who wanted to know more: The Oneida Disaster!…

- Articles in newspapers and periodicals provide personal accounts written at the time of the event and for many years after. In 1914, the Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute published U. S. S. Oneida, Lost January 24, 1870, in Yeddo (Tokyo) Bay, Japan. Reminiscences by Rear Admiral O. W. Farenholt, U. S. Navy, RetiredExternal. Farenholt was the last sailor to bid farewell to his friends and disembark from the Oneida at Yokohama, before she set sail on her ill-fated journey.